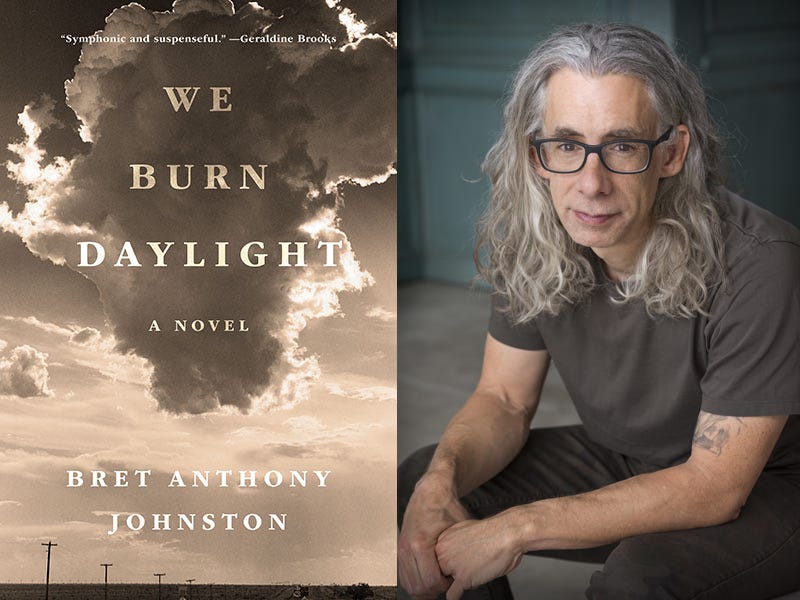

Bret Anthony Johnston writes for the same reason he reads: to find out what happens next. That’s a good thing, because otherwise he might never have finished his latest novel, We Burn Daylight, a book that fought him for years before abruptly vanishing (along with the laptop it was written on) through the freshly shattered window of a rental car. That ill-timed burglary was the dark night of the soul in an already challenging project, Johnston says, but ultimately it cemented his commitment to finishing it.

“If I were ever going to give up on the book, it was going to be right there,” says Johnston. “And I had the chance to do it. Nobody had read it at that time, I didn’t have a book deal. But it just felt like ‘I’m too invested, I want to see how the story ends.’”

Now you might be asking, because I sure did, “How could he be that far into writing a book without knowing how it ends?” I write without an outline all the time, but I write short things. I’d always assumed you couldn’t write a novel, or at least not a good novel, without first covering a wall with chronologically ordered scenes on index cards. But while that may work for some writers, it doesn’t for Johnston. The author of Corpus Christi: Stories and the best-selling novel Remember Me Like This and director of UT’s Michener Center for Writers, he prefers to work with no “point B” in mind. Instead, he talks about writing as though he is uncovering preexisting facts — as a process of discovery rather than construction.

“Through decades of trial and error I have realized that if I know how something ends, I can’t write it. It is a level of boredom that cannot be overstated,” Johnston explains. He speaks slowly and carefully, as though he’s crafting his conversational sentences with the same precision as his written ones. “If I’m going to commit to something that is going to take years, in this case a decade, to write, I have to believe it has the potential to surprise me.”

The story told in We Burn Daylight will sound familiar to some as it pulls inspiration from both recent history (the infamous 1993 Waco siege, which led to the deaths of 75 Branch Davidian members and leader David Koresh) and earlier fiction (Romeo and Juliet). But don’t rush to their respective Wikipedia summaries because Johnston’s characters quickly stray from those plots. While he read numerous books about Waco in preparation for writing the novel, history is merely the jumping off point, not the landing.

Through alternating chapters narrated by its young protagonists, the book introduces us to Roy, a sheriff’s son whose secret hobby is picking locks, and Jaye, a wisecracking outcast who impulsively tags along on her mother’s cross-country road trip to join Koresh-eque spiritual leader Perry Cullen. Jaye and Roy meet and fall in love a few short months before events mirroring history overtake their fictionalized Waco. The resulting novel is simultaneously a page turner and a slow burn. In the impatient 24 hours between finishing the Amazon preview and obtaining a full copy of the book, what I was waiting for was less the progression of the love story or the looming tragedy than just the chance to spend more time with these characters.

The initial spark for We Burn Daylight was a conversation Johnston overheard in which the speaker described having unknowingly worked for years alongside a Branch Davidian member in Waco and learning about their colleague’s involvement with the group only later, while watching the news after the disaster. That story stuck with Johnston, and he found himself wondering how it would feel to discover something so startling about somebody you thought you knew. But he didn’t decide to write the book until he started thinking about what that experience would be like not for an adult coworker but for a kid — specifically for an ordinary 14-year-old boy who meets a new girl in town with no idea of how wildly different their situations are.

That tension of not knowing is reflected in the novel’s timeline. Roy and Jaye’s chapters don’t temporally align at first, and so we read about Roy’s first sighting of Jaye while Jaye is still watching her mother fall under Cullen’s spell back home. From Roy’s perspective, Jaye initially appears as an archetypal manic pixie dream girl, all mystery and no concrete backstory, inexplicably wearing a gas mask during their first conversation. But as the two get to know each other, talking for hours on the phone because meeting in person is difficult, their narratives converge, like the rhythms of a longtime couple taking turns relaying the story of how they met.

Johnston is a big advocate for doing extensive research throughout the writing process, and it is the large and small fruits of that labor that give the book so much texture: the stores in an abandoned shopping mall, the martial arts movies favored by adolescent boys, the mechanics of a lock designed to be unpickable. Johnston even learned to pick locks to better understand Roy’s adolescent obsession.

“Research, for me, liberates the imagination rather than confining it. Maybe it liberates it by confining it,” Johnston says, citing a moment in which a detail gleaned from reading about locks gave him fresh insight into the seemingly unworkable moving parts of the story.

The key, so to speak, to applying all this acquired information was figuring out which pieces served the story Johnston wanted to write. As it turned out, the least useful material was that about David Koresh.

“There’s been so much written about Koresh that I couldn’t find a crack for the imagination to come in,” he says. “Everything you want to know about that man is there, there’s nothing left to discover. So, the character of Perry is where I’ve diverged most from history.”

Since Perry himself never narrates a chapter of We Burn Daylight, impressions of him often come from various insiders and outsiders interviewed on a fictional present-day podcast whose transcripts are interspersed between Roy and Jaye’s chapters. Among the most sympathetic voices is that of Roy’s father, who views Perry and his followers as eccentric but not unreasonable and criticizes other law enforcement agents for favoring force over negotiation in dealing with the group. But the major insights come from Jaye, who meets Perry midway through his transformation from harmless charmer of lonely women to zealous religious leader with apocalyptic ambitions. Through her jaded teenage lens, Perry emerges as alternately grating and charismatic but always deeply flawed. “A clown in want of circus,” Jaye calls him early on, and, in a less generous moment, “my mother’s dipshit lover.”

In an effort to be unbiased, I tried to avoid the word “cult” while talking to Johnston. According to the audio recording of our interview, I failed just 12 minutes in. It’s hard not to. The word is easy shorthand for the allure of such subject matter — the unusual beliefs, the deviations from social norms, and the conditions of communal living. We Burn Daylight delivers these lurid tidbits but refuses to pass judgement on its characters or blame them for their fates. Both in our interview and in his writing, Johnston contends that “cult” is not a useful distinction for describing the members of his fictional group or the Branch Davidians, who were themselves an offshoot of Christianity dating back to the mid-20th century. “How is one belief system, not matter how marginalized, different from something we’ve accepted as conventional and healthy and unassailable just because it’s been around longer?” he asks.

And although the book is sprinkled with easter eggs for readers of Shakespeare (and occasionally Ovid), it is no more bound to the tale of Romeo and Juliet than to that of Koresh. Most notably, We Burn Daylight does not end in a misunderstanding-induced double suicide. But it’s also not what I would describe as a happy ending, although many readers have reached exactly that conclusion, to Johnston’s astonishment. He’s careful not to favor any single interpretation of the book and welcomes the plurality of readings, but at the same time he appears genuinely confused that so many people found the ending comforting.

“I hope it feels like a satisfying ending, I hope it feels like a rewarding culmination to a reader having given this book their precious attention,” Johnston says, and he’s not being snide with the word “precious”, as he knows all too well how limited a resource our attention is. “But given the material of the story, I don’t know that a happy ending is possible, and I tried to honor that.”