By Daniel Oppenheimer

—

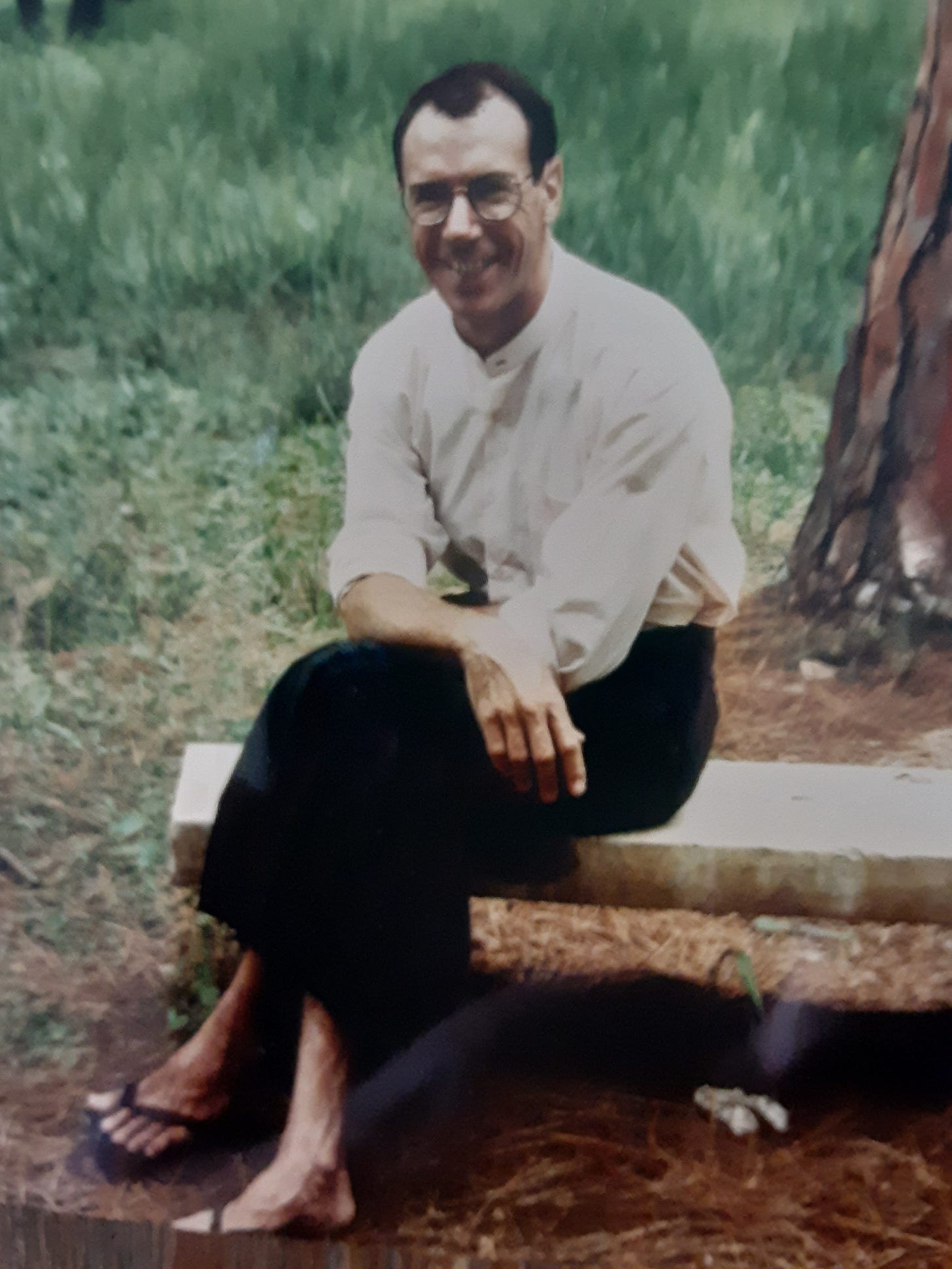

Ward Keeler is a professor of anthropology at The University of Texas at Austin. His research focuses on performing arts, language, gender, and hierarchy in Indonesia and Burma, and he is the author of, among other books, Burmese: A Cultural Approach (Hong Kong University Press, 2021) and Traffic in Hierarchy, Masculinity and its Others in Buddhist Burma (University of Hawaii Press, 2017).

I spoke to Ward about many things, including his childhood interest in becoming an anthropologist, his study of Javanese shadow plays, the turn in anthropology away from studying faraway places, and his abiding interest in hierarchy in human relations.

To give you a taste, here’s a (lightly edited) passage in which Ward and I discuss how hierarchy plays out in cultures, like American culture, where the consensus ideology denies its significance and prevalence:

Ward Keeler: American politics and the constitution are riven with these contradictory attitudes toward status and who deserves to be equal and who doesn't.

Daniel Oppenheimer: You can't wish away hierarchy in human nature. It seems to be just built into it, whether it's built into our biology or just the nature of things interacting with each other. Because it's in the animal kingdom, too. Wherever there's difference, wherever there are inequalities in power—which is to say everywhere—there will inevitably result some form of hierarchy. And I would say implicit and explicit in some of your work is that we get into trouble when we pretend that what's there isn't there.

Keeler: Yes, that's right. At a certain point in my undergraduate course, I always say to the students, “What would you think if I just said, ‘Just call me Ward.’”

And the point is that that's actually quite disingenuous, and really quite fake, because I still grade them at the end of the semester. I have not actually given up any power I exercise over them.

Oppenheimer: It’s worse than that. It's not just fake, but to the extent that you actually deprive yourself of some of the charismatic power of the professor, you're actually depriving them of some of the benefit of education, which can involve putting yourself under the sway of the sort of pedagogical charisma of a professor.

Keeler: Yes. As a matter of fact, I’m in the process of writing a fellowship application and the title of my proposal is “Hierarchy and the allure of subordination.” In all of our insistence on agency and autonomy and so on, we rather neglect the fact that subordinating yourself can have real appeal. It can be an attractive force.

Oppenheimer: That includes more salacious forms of subordination, but also just being a student and wanting to be able to look up to a teacher. My wife is a psychotherapist, and she will say, “Look, it helps their therapeutic process to invest me with authority. It helps them grow and heal and repair wounds to believe that I'm in possession of wisdom that they don't have or insight that they don't have.”

In some cases, this involves projection, but it's a healthy projection. And for that matter it probably helps to heal medically to invest your doctor with a presumption of authority and power.

Keeler: Actually, that's something I bring up with students, which is that Americans tend to say, “Oh yeah, using first names is always a good idea. It's so much more friendly and so on.” But we don't want to do that with our medical professionals. We insist upon calling them doctor so and so.

And I have very self consciously altered my practice. So I say to my doctor, “Hey, Mark, what do you think about this?” Precisely because I need to remind myself that he doesn't know everything. He may not be able to solve this. He’s a person like I am.

Listen to the whole thing. It’s super interesting!

Share this post